Detecting Lies on Earnings Calls

Around the world, trust in large institutions and their leaders is at a distinct ebb. The 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer, which measures trust in government, business, and other institutions, found that trust in CEOs fell to a record low 37 percent in 2017, down from 49 percent in 2016.

Of course, post-truth era or not, business executives don’t generally go around spouting unverifiable facts and numbers. That’s in part because they face stiff penalties for doing so. If a CEO says earnings per share were $1.50 last quarter when, in fact, the company reported earnings per share of 64 cents, investors will quickly punish the company and its stock. It’s pretty easy to measure whether a CEO is being truthful about results. But there is a lot more nuance involved when it comes to measuring credibility, which is earned by speaking without obfuscation and meaning what you say. And that’s precisely what Joel Litman, chief executive officer of Valens Research in Cambridge, Mass. — a financial research firm that offers forensic and uniform accounting analysis to clients — has in mind as he prepares his lie detector equipment for the coming round of year-end earnings reports.

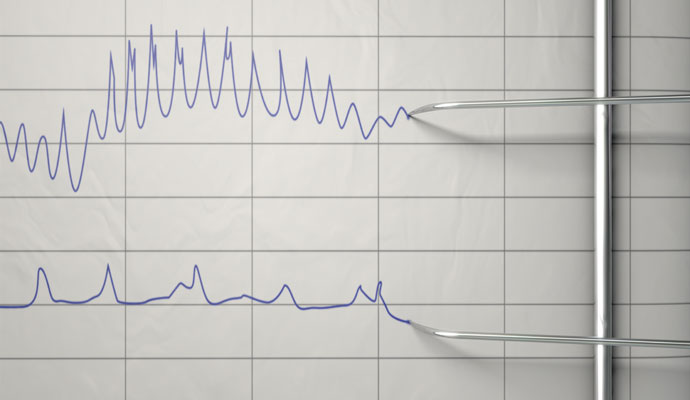

Hedge fund managers and other large investors hire forensic analysts to sit in on corporate earnings calls. The first half of such calls tend to be heavily scripted, as top leaders run through the results. But in the second half, executives answer questions from equity analysts — or evade those questions — and therefore are working without a script. That’s when the Valens analyst keeps an eye glued to the firm’s proprietary electro-audiogram (EAG) system, which measures voice patterns. Think of the digital audiogram as a sophisticated lie detector test. In all, it maps a total of 15 markers that gauge whether the speaker seems to believe his or her own words based mostly on inflection — whether the voice seems stressed or hesitant, grows louder or softer, speeds up or slows down.

The effectiveness of the EAG depends on the psychological principle of cognitive dissonance — the physical discomfort that arises in most people when they try to hold two opposing ideas in their brain at the same time. If the audiogram indicates a high level of speaker confidence, Valens reports to its clients that the leaders of Company X seem to have a firm grasp on their plans for future growth or for confronting challenges. That might give investors a good reason to buy Company X stock. By the same token, a low confidence score might be a clue that investors should stay out of the stock or short-sell it.

Valens and others in the business of detecting cognitive dissonance, such as Business Intelligence Advisors in Boston, which is run by former Central Intelligence Agency investigators, are seeking to understand how the judgment and integrity of company leaders can affect a company’s valuation over time. Earlier this year, the CFA Institute, an international association for chartered financial analysts, published a book with the very self-explanatory title Lie Detection Guide: Theory and Practice for Investment Professionals. Laura Rittenhouse, who runs the consulting and training firm Rittenhouse Rankings in New York, analyzes written messages, especially CEO shareholder letters, and ranks companies for wording that indicates candor and transparency versus what she euphemistically calls “balderdash.” Examples of balderdash include the phrase “in a dynamic operating environment characterized by unexpected events around the world,” which appeared in the annual letter of a large bank, and “we face stiff competition, but our future is within our control,” from Walmart’s 2016 annual report. (“When are there not unexpected events?” says Rittenhouse. “And no one’s future is completely under their control.”)

Those in the business of detecting cognitive dissonance are seeking to understand how the judgment and integrity of company leaders can affect a company’s valuation over time.

Litman, a former Credit Suisse analyst, started Valens in the very rocky year of 2009. “We should have had our heads examined for launching a startup venture in the middle of the downturn,” he says. But Litman wanted to provide the kind of all-encompassing analysis that was mostly missing on Wall Street at the time. The firm has analyzed more than 20,000 earnings calls since its inception. In 2009 and 2010, it wasn’t hard to find executives from banking and other industries whose voices indicated tension when they said things were getting better. Three years ago, Valens researchers observed a lot of highly questionable markers in the earnings calls of oil exploration firms, which were then grappling with low prices and excess supply. Soon after, not at all to Litman’s surprise, the sector nearly collapsed.

Take a statement like “we’re expanding at full steam.” If executives show a sense of discomfort saying that the macro factors indicate an economy in decline, then we might expect, when the economy is doing well, that they’ll it with conviction. That is exactly what Litman has found in the last couple of years: The confidence markers are strong for most large companies.

Still, the bull market hasn’t put balderdash-detection firms out of business.

For one thing, companies have to explain what they’re doing to counter disruption. Valens has been sounding alarms about retailers losing steam to Amazon, for example, since around 2012. The firm’s analysts noted several retail companies they thought had more potential to thrive than most, including L Brands, the parent company of Victoria’s Secret and Bath & Body Works. When Valens was hired by investors to use its audiogram in the company’s first- and second-quarter earnings calls this year, it found further confirmation of its belief that the company was going to be able to, as a Valens research report put it, “streamline operations, while still driving innovation that consumers wanted.” But it turns out that 2017 hasn’t been a great year overall for L Brands. Sales dropped after Victoria’s Secret stopped selling swimwear and apparel to concentrate on its flagship lingerie, only to find that Amazon was undercutting that business.

When the company convened its second-quarter earnings call in August 2017, the stock was falling. However, in an answer to an analyst’s question about inventory, Stuart Burgdoerfer, chief financial officer of L Brands, said, “It is up a little bit but not significantly, and there’s a little bit of timing involved. But our commitment to manage inventory in line with sales was as strong as ever.” The CFO didn’t deny that there was a challenge. More to the point, his voice pattern as detected by Valens’s audiogram indicated that he believed what he was saying. The company’s stock has since started to rebound. A coincidence? Possibly. But Litman’s investor clients are looking for an edge that comes from an analysis of whether all the measures of a company’s financial health — equity value, debt, and a senior management team that has a firm grasp on reality — come together.

Rittenhouse believes it’s more important than ever for corporate leaders to be forthcoming in times of significant disruption because managers who are honest about what they’re doing — honest with themselves and their shareholders — will be compelled to develop a clear strategy. “Delusional speech creates a cognitive dissonance that, in some sense, shuts down the brain,” she says.

The good news is that companies can turn around a habit of obfuscation. Examining Walmart’s latest annual report, Rittenhouse found the letter a big improvement over last year’s. It contained clear language about factors the company could actually control, such as, “In the U.S., we’ve delivered positive comp store sales for 10 consecutive quarters and we’re hearing from our customers that their experience continues to improve.” You don’t need a computer program to detect the realistic confidence in that statement.

Published at Tue, 12 Dec 2017 06:00:00 +0000